Showing posts with label drones. Show all posts

Showing posts with label drones. Show all posts

Sunday, March 13, 2016

Working with PhotoScan in the cloud

Back in 2012 when I first started flying drones to make high-resolution photomaps (e.g., strapping a first-generation GoPro to the bottom of a balsa-wood DIY drone and hoping for the best), there were few options for processing the photos.

Basically, if you didn't have access to $2,000 software, you only had Microsoft Image Composite Editor (ICE) to stitch together the photos into mosaics. Fortunately, much has changed since then.

In a window of just two years, a number of software solutions became available. VisualFSM brought free, open-source photogrammetry to tech-savvy hobbyists and researchers. There was Autodesk's 123D catch, which could be used with drone imagery in a pinch. Pix4D came about in 2011, which later gained a huge market share in the professional UAS space. I won't get into all the options, but there's a fairly comprehensive table on Wikipedia that you might wish to look at.

The solution I use most often today is Agisoft PhotoScan. The feature set of the standard version is somewhat limited compared to solutions designed specifically for UAS use, but it's also easy to use, the software license is comparatively cheap, and it runs on ordinary desktop machines.

Many photogrammetry services are run in the cloud (123D catch, Pix4D, DroneMapper), which has its benefits. You don't have to upgrade your machine to run complex models. You don't have to tie up a computer for hours while it's processing 500-1,000 photos. You can start a job in another country, send your images to the cloud instance, and by the time you arrive back home, your job can be done.

But processing in the cloud can mean paying fees by the month or by the job. If you like paying a one-time fee for a license, the cloud may not be the most attractive solution.

Thankfully, PhotoScan can be run in the cloud. While it does mean incurring hourly fees for computer time and cloud storage, it can also help in a pinch when you're working on an especially large project.

Tags:

3D modeling

,

Amazon

,

AWS

,

drones

,

EC2

,

photogrammetry

,

PhotoScan

Tuesday, December 16, 2014

Here's a holiday gift guide to help you get started in drones

While drones have some great potential both as a tool and an educational hobby, it can be rather intimidating to get started.

There's just so many platforms and widgets to choose from, and it seems every day someone is launching a new type of drone. As I pointed out in a recent post on the sensor journalism Google group, I actually think the market might be bottoming out for creating drone hardware, so hopefully the selection process will be easier in the future.

Complicating the matter is that drones can crash or fly off if they lose a GPS lock, risks that are substantially higher when you're just starting off. Having a $1,000 drone fly off with a $300 camera is not a fun or rewarding introduction to drones and remotely piloted aircraft systems.

So, I've made a holiday gift guide for Make Magazine to show people options for the beginner, intermediate, and advanced drone operator.

If you've never flown a remote controlled aircraft before, I highly recommend something like the Walkera Ladybird. Myself, I've had a fair bit of luck with Quanum Nova, which has an attractive feature set and price for intermediate operators who don't need to loft heavy cameras or go beyond visual line of sight.

Whatever drone you end up choosing for yourself or a special someone, remember to drone responsibly. That means, among other things, picking up an AMA membership and the complimentary insurance that comes with it.

Tags:

diy drones

,

drones

,

getting started

,

MAKE

,

Make Magazine

,

makerspace

,

RPAS

Thursday, February 27, 2014

A call for journalists and makers to join hands around IOT and evidence-based journalism

Writing for Al Jazeera English, D. Parvaz reported on a recent conference for atomic experts organized by the International Atomic Energy Association (IAEA), where it was remarkably difficult to get answers from atomic experts.

The conference, titled “International Experts’ Meeting on Radiation Protection after the Fukushima Daiichi Accident – Promoting confidence and understanding,” was generally closed to the media. Journalists received presentations on USB drives, but were not given any opportunities for Q&A. The media handlers were pleasant, but not very helpful, Parvaz noted.

Great! I requested an interview with the IAEA Scientific Secretariat, Tony Colgan (no can do). Or a statement on why the conference was closed to the media (not so much). How about an IAEA expert on the effects of radiation on sea life? (Nope).

For a conference designed to “promote confidence and understanding” with the public, there was very little engagement with the public. Despite this, Parvaz did find one group of presenters who were very helpful and answered her questions.

Tuesday, February 4, 2014

A bug's eye view, brought to you by a nano quadrotor drone.

What's better than a tiny drone that buzzes like a bee through offices and hallways? How about a tiny drone shielded with a 3D-printed frame, controlled by a Raspberry Pi base station, and equipped with a miniscule video camera and transmitter?

Tags:

3d printing

,

aerial drones

,

Bitcraze

,

Crazyflie

,

drone journalism

,

drones

,

drones for good

,

FPV

,

maker

,

nano copter

,

nano drone

,

nano transmitter

,

rapid prototyping

,

STEM education

,

unmanned aircraft systems

Monday, January 13, 2014

A discussion on deploying drones for international development

Last month, Deutsche Post DHL transported six kilograms of medicine from a pharmacy in Bonn, across the Rhine River, to its headquarters.

This wouldn't have made international news, except that DHL accomplished this with an unmanned aircraft system - commonly known as a drone.

This came less than a week after Amazon's Jeff Bezos claimed his company would deliver products to customers' doorsteps via drone in three or four years. Regulations and technological hurdles would make Bezos' plan all but impossible in the US near-term, but DHL proved that with proper planning and logistics, you could deliver small parcels with small drones today.

On January 22, The International Research and Exchange Board, or IREX, will be hosting a "deep dive" discussion on how this same technology could benefit international development.

Tags:

deep dive

,

drone journalism

,

drones

,

drones for development

,

drones for good

,

IREX

,

RPAS

,

sUAS

,

UAS

,

UAV

Monday, November 25, 2013

There's been a big uptick in drone research over the last decade

Recently, I was tasked with producing some basic citations on unmanned aerial vehicles, more commonly called drones, for a new grant proposal. As you could imagine, it was not hard to find a cornucopia of papers reflecting the many novel uses for the technology.

What might surprise some, though, was the sheer increase in drone research, how popular these papers are in the academic world, what that research trying to accomplish, and who was funding it.

Tags:

drone research

,

drones

,

research

,

UAS

,

UAV

,

UAV research

,

unmanned aerial vehicles

,

unmanned aircraft systems

Monday, September 23, 2013

Drones, journalism, and the peak of inflated expectations

It's a story that's been repeated time and time again with emergent technology. Researchers publish some new breakthrough, and the press grabs hold of the news release and begins extrapolating stories about how the new tech could revolutionize our lives. Expectations build as ideas bounce within the media echo chamber, pitchmen evangelize audiences at the trendy tech conferences, and venture capitalists make power plays in the market.

Everyone wants a piece because the sky is the limit, and the sky is the limit because everyone wants a piece.

Products finally hit the market, and eventually, reality sets in. Like the doomsayers who predict apocalypse time and time again, the prophesied miracles fail to materialize. The technology is immature. Deliverables fail to match objectives. Most importantly, the technology was overvalued, and an adjustment takes place.

This "hype curve" -- rising expectations, peak interest, and curbed enthusiasm -- doesn't happen to every piece of technology that comes around. But this bubble does happen with surprising regularity. Every year, Gartner, a tech research corporation, produces a report that attempts to identify where various technologies are riding on this bubble.

Gartner released its latest report, "2013 Hype Cycle for Emerging Technologies," last month. In it, the company prognosticates that drones and other unmanned technologies are coming up to that peak. At that point, the unmanned systems sector might be in for some pain.

Tags:

data journalism

,

drone boom

,

drone hype

,

drone journalism

,

drones

,

Gartner

,

hype curve

,

precision agriculture

Friday, August 16, 2013

Even with a ton of drone regulations, there was a ton of innovation at the SUSB Expo

|

| An MLB Company representative shows the company's Super BAT's camera gimbal system to an audience member during the SUSB Expo, in San Francisco, CA. |

It's not very often you get the chance to watch the birth of a multi-billion dollar industry firsthand. But if we are to believe the Association for Unmanned Vehicles and Systems International (AUVSI) economic report, which estimates the unmanned aviation industry should reach $82 billion by 2025, that's exactly what happened at the first-ever small business expo for unmanned aircraft, the SUSB Expo, in San Francisco.

"It's like being in Steve Job's garage," said Agriflight's Bruce Parks, as reported by Robohub's Andra Keay.

Tags:

3DRobotics

,

Chris Anderson

,

drones

,

drones for good

,

San Francisco

,

SUSB Expo

,

sUSBExpo

,

unmanned aircraft

,

unmanned aircraft systems

Monday, July 22, 2013

UAVs Pros Cons in Toronto: safety and dialogue are keys to legitimacy

|

| Ian Hannah of Avrobotics.ca displayed his professional hexcopter at the UAVs Pros Cons Symposium in Toronto. |

The townspeople may or may not be "real" about their proposed law, given the likelihood of people being injured by gunfire or falling drones, but fear of unmanned aircraft systems (dronephobia?) is real. This fear is rooted in a disconnect between popular media, and the actual uses and potential for the technology.

UAVs Pros-Cons was an effort bring expert knowledge to the public, while at the same time providing a discussion of many of the legitimate concerns over drones and their uses.

Tags:

Alexander Hayes

,

Andrew Clement

,

Avner Levin

,

Avrobotics.ca

,

drones

,

Ian Hannah

,

Katina Michael

,

pros cons

,

Ramona Pringle

,

Ryerson

,

sUAS

,

Toronto

,

UAS

,

UAVs

,

UAVs Pros Cons

Thursday, July 11, 2013

Why the word "drone" is scaring neighbors, creating bad legislation, and blocking an economic boom.

This disruption had a passing resemblance to what happened to other American industries. The hard work once done by skilled, human hands was now being automated by the calculating actuators of a machine.

Automation had long since dominated the appliance, automotive, and electronics industries. But this was a brand new territory – aviation.

The reduced price and size, and the increased reliability and capability of processors, sensors and batteries meant unmanned aviation had been unleashed. A nouveau DIY revolution meant that basements and garages were once again incubating nascent technology, just as they did in the 1970s when the personal computer was being developed.

The silver lining is that the cost of search and rescue, disaster relief, monitoring wildlife, guarding endangered animals from being poached, and even medication delivery to underserved populations all could be slashed.

Like many other small startups in the unmanned aviation industry, my friend and her husband saw an opportunity. And despite criticism of slow progress on regulations, the Federal Aviation Administration also sees it. The FAA estimates that the market for commercial unmanned aerial systems will eventually reach $90 billion.

The Association for Unmanned Vehicles and Systems International (AUVSI) believes there will be an economic impact of $13.6 billion within 3 years that unmanned aircraft are integrated into the national airspace.

Where to start? What better way to get acquainted to the industry than attend one of the premier industry conference in the nation, hosted by AUVSI?

She learned about new applications for unmanned aircraft. She listened to a UAV operator who used his homemade robotic aircraft to assess flood damage in Thailand. The information gathered from the aerial vehicle allowed the government to make decisions that mitigated flooding in the country’s capital.

This was great. But when it came to talk shop, things became awkward when she used a five-letter word that began with the letter “d.”

“The conversation would just stop,” she said. “Just completely stop dead.”

Tags:

AR.Drone

,

AUVSI

,

Chris Anderson

,

diy drones

,

drone etymology

,

drones

,

drones for good

,

Marc Corcoran

,

Oregon SB 17

,

origin of the word drone

,

rise of the drones

Friday, May 10, 2013

Life-saving rescue could be game changer for drone adoption

Search and rescue often is touted as one of the areas where unmanned aircraft, commonly called drones, can do the most good with existing technology.

SAR, as it's called in the business, will only make up a small part of the economic pie for the unmanned aircraft industry, according to an economic report by the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI). But out of all of the potential applications, due to the personal impact and high news visibility of missing persons, it has the potential to be the greatest asset in public acceptance of drones.

If a positive public perception translates into acceptance, history might show that Thursday was a game-changer in terms of domestic drone adoption.

Tags:

Dragan Flyer

,

DraganFlyer rescue

,

drones

,

RCMP

,

SAR

,

search and rescue

,

UAVs

,

unmanned aircraft systems

Wednesday, May 8, 2013

You can't always get the the drone you want, but if you try a laser you'll get what you need

The "perfect" small unmanned aircraft, commonly called a drone, might still be several generations away. But like Moore's law, those generational cycles are getting shorter and shorter.

Chris Anderson of 3DRobotics suspects we're closing in on the drone equivalent of the Mac: a relatively affordable, accessible, and most importantly, practical piece of technology that can be deployed every day.

Tremendous headway has been made with multirotor technology (the heicopters, quadrotors, hexcopters, octocopters, and what have you). The market is quickly becoming flush with a variety of these aircraft, to the point where several options are available for each price bracket.

There's everything from $300 hobbyist rigs from big-name RC and electronics manufacturers, to $1,000 semipro setups from DJI and 3DRobotics, to $10,000 rigs that can loft, pan and tilt a DSLR or DV camera. The differences between each step may be as simple as stronger frames, larger motors and higher-capacity batteries.

A drone of your very own, from novice to pro. Sometimes no assembly required.

For the time being, however, it's still useful to have the technical know-how to put one together. It's even more useful to know how to fabricate a drone, or fabricate parts to suit your specific application.

Tags:

3DRobotics

,

APM 2.5

,

citizen drone journalism

,

drone journalism

,

drones

,

epilog laser

,

fabrication

,

fixed wing

,

laser cutting

,

maker

,

quadcopter

Monday, April 8, 2013

On engaging the public on privacy, journalism, and drones.

Journalists might be familiar with the quote by US Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, who once wrote "Publicity is justly commended as a remedy for social and industrial diseases. Sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants."

Journalists seeking to use unmanned aircraft would be wise not to just apply that concept of uncovering the truth about others, but also to make the public aware of how they intend to use "drones."

While the response journalists get from the public might be unexpected, the answer is not to become defensive or rely on ad-hominem arguments. Whatever your station in journalism, you are as much a servant to the public as any of the officials you interview.

The following is copied from the post I wrote for sUASNews.com.

Journalists seeking to use unmanned aircraft would be wise not to just apply that concept of uncovering the truth about others, but also to make the public aware of how they intend to use "drones."

While the response journalists get from the public might be unexpected, the answer is not to become defensive or rely on ad-hominem arguments. Whatever your station in journalism, you are as much a servant to the public as any of the officials you interview.

The following is copied from the post I wrote for sUASNews.com.

Tags:

3DRobotics

,

CERI

,

Chris Anderson

,

drone journalism

,

drone law

,

drones

,

In Focus

,

law

,

Nancy Cooke

,

NPR

,

privacy

,

US drone law

,

WILL AM580

Wednesday, March 20, 2013

"Drone" over SXSW provides aerial view of NASA's shiny new space telescope

Unmanned aircraft made their South By Southwest debut this year, and prominently so. A session with Chris Anderson, former Wired EIC turned full-time head of 3D Robotics, and Ryan Calo of The Center for Internet and Society at Stanford Law School, among others, included a discussion on the many commercial uses for UA.

On the same day, at the Palmer Events Center, near a full-scale replica of NASA's James Web Space Telescope, another panel was being held that featured a live demonstration of an unmanned system.

Tags:

AR.Drone

,

drones

,

drones over sxsw

,

James Webb Space Telescope

,

mike north

,

NASA

,

ReAllocate

,

STEM education

,

sxsw

,

sxsw 2013

,

sxsw interactive

,

sxswi

,

unmanned aircraft

,

unmanned aircraft systems

Tuesday, February 19, 2013

World's most popular consumer drone gains autonomous flight

Since it was introduced in 2010, the AR.Drone has been a success among hobbyists, hackers, engineering students, drone journalists, activists, and aspiring UAS (Unmanned Aerial Systems) operators. Produced by the French wireless products manufacturer Parrot, this camera-enabled quadrotor can be controlled over WiFi via iOS or Android-enabled phones and tablets.

This has been the go-to item for many news organizations trying to understand the new world of UAS without a tremendous investment. The Sydney Herald recently used one to help bring context to their story about privacy concerns amidst the proliferation of "drones."

A news crew in Florida also tried using an AR.Drone to get a better view of a live event, but they were chased out of the sky by angry bees.

Since launch, it has sold over 300,000 units. That's ten times the number of UAS that the FAA anticipated would by flying in American airspace... by 2020.

A selling point of the RC aircraft from the beginning has been augmented reality dogfights with other AR.Drones, facilitated by on-board image recognition. Parrot recently unveiled another addition to the drone's list of AR abilities -- a GPS receiver.

Tags:

aerial drones

,

AR Drone

,

AR.Drone

,

drones

,

FAA

,

GPS

,

Sydney Herald

Wednesday, January 9, 2013

Droneveillance, and blogging for the International Symposium on Technology and Society

Lately I've found myself blogging for the International Symposium on Technology and Society, or ISTAS. It's an annual conference sponsored by IEEE (the Institute of Electric and Electronic Engineers), which as its name suggests, focuses on the impact that evolving technologies have on everyday life. This year's conference will pay special consideration to the future of the smart infrastructure and surveillance:

In a world of smart things like smart lights, smart toilets, smart grids, smart meters, smart roads, and the like, what happens when you have "smart people" (i.e. put sensors on people)? What do we make of the growing numbers of businesses like department stores and restaurants that prohibit cameras, yet display QR codes that require cameras to read and understand?It's not just about surveillance, either. Surveillance has a specific meaning, which refers to observing people or objects from an elevated position.That means surveillance is conducted by law enforcements and governments. Sousveillance, on the other hand, means observing or recording from below. When average citizens, as opposed to the government, do the recording, that's sousveillance.

How about droneveillance? Unlike fixed cameras, drones are highly mobile platforms for a variety of remote sensing devices. They're agile, relatively silent (depending on the altitude), and can even fly indoors. They've gotten especially smart at negotiating obstacles and mapping unfamiliar terrain, and they can work as a team to provide comprehensive monitoring.

Tags:

drone journalism

,

drones

,

droneveillance

,

IEEE

,

ISTAS

,

river of blood

,

sousveillance

,

surveillance

,

UAV

Friday, November 9, 2012

We need more drones because we’re having more big disasters.

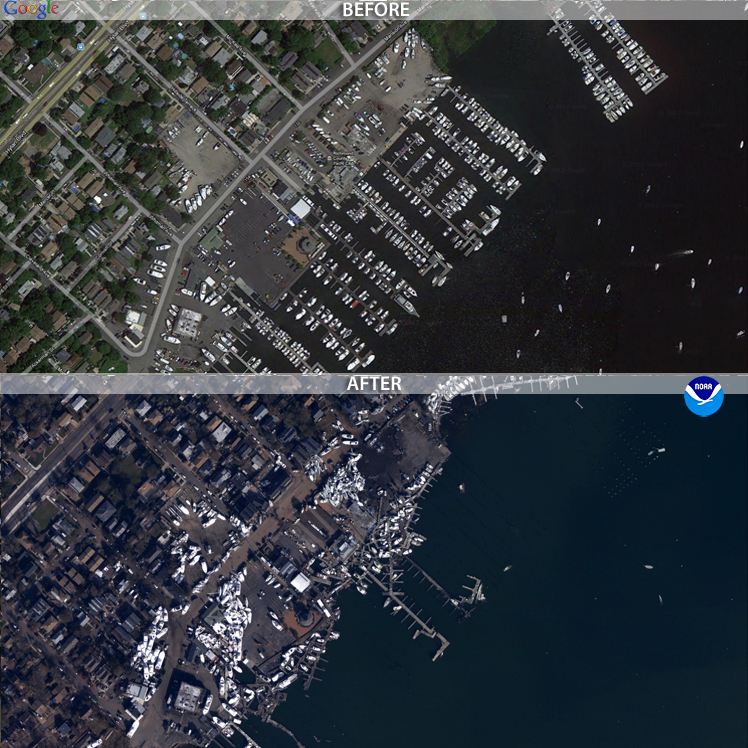

The images of an inundated New York City certainly were eye-catching. But it isn’t until you start parsing the data that you start to really understand how bad things got for the East Coast.

Some of the most startling stats: winds pegged at 90 miles an hour when Sandy made landfall as a tropical storm. It left 185 dead between Jamaica and its terminus in the US. It was the second costliest hurricane in recorded history after Katrina, with $52.4 billion in damages. Five thousand commercial airline flights cancelled. Across 26 states, up to 80 million were affected. Eight and a half million people without power after the storm.

Even 11 days after the storm, with freezing winter temperatures closing in, 428,000 in New York and New Jersey remain without power.

Aon Benfield, an insurance broker that specializes in catastrophe management, crunched the numbers and found something just as remarkable about hurricane/tropical storm Sandy. Well, perhaps not so much about the storm itself, but how it fits into recent weather events and climate change in general.

“Devastating Hurricane Sandy was the eleventh billion-dollar weather-related disaster in the U.S. so far this year, and the most expensive,” wrote Wunderground.com’s Jeff Masters, of Aon Benfield’s latest report. “This puts 2012 in second place for most U.S. billion-dollar weather disasters behind 2011, when NOAA's National Climatic Data Center (NCDC) counted fourteen such disasters.”

Meanwhile, climate scientists noted that not only did global warming make such a historic slew of storms possible, it also made the sea level rise, thus increasing the damage to coastal areas.

“Sandy threw the ocean at the land, and because of global warming, there were about eight inches more ocean to throw,” wrote Chris Mooney on The Climate Desk. “As the water level increases, the level of damage tends to rise much more steeply than the mere level of water itself.”

When Thailand was flooded in 2011, the government contracted a drone to scout out where flooding had occurred, which helped make decisions about where and when to release flood gates. The contractor flew more than 60 flights over a period of 45 days, and claimed that the data obtained from those flights helped prevent the city of Bangkok from suffering more during that catastrophe.

That same year, back in the states, freelance journalist and storm chaser Aaron Brodie took sweeping shots of the Jersey Shore with his own multicopter before and after Hurricane Irene. He uploaded this footage on YouTube, but amended his post after Sandy:

“Irene was child's play in comparison to Superstorm Sandy. In fact, there was no real damage from Irene,” Brodie wrote.

The public wasn’t able to obtain coverage from drones for Sandy. Some news sites did, however, post before and after photos of New York and New Jersey. These post-sandy aerial photos were obtained by the National Geodetic Survey, with the help of NOAA’s King Air and Twin Otter remote-sensing aircraft. The photos were set side-by-side with historic satellite imagery, allowing users to drag these images to do their own comparisons.

Because of the prohibitive cost of aerial photomapping, these images were gathered by government agencies. But, if FAA regulations allowed it, the job could have easily been done with a $1,000 aerial drone. That puts it within reach of even independent and backpack journalists. Or concerned members of the community.

If the climate models hold true, there’s going to be more “superstorms” like Sandy every year. There will be more billion-dollar disasters, more lives lost, more power outages, and the public will need more information about how those disasters are affecting their communities.

Drones are especially capable of giving quick data on the scope, or extent, of large-scale disasters. Now is the time for journalists to learn and perfect tools like the drone to give the public that information.

Photo at the top of the post is of post-Sandy flooding in Haiti, via the Flikr photostream of United Nations Stabilization Mission In Haiti.

Tags:

disaster reporting

,

drone

,

drone journalism

,

dronejournalism.org

,

drones

,

Hurricane Sandy

,

natural disasters

,

Sandy

,

sUAS

,

UAS

,

UAV

Thursday, October 11, 2012

The case of Chicken v Bomber, and how it might impact drone law

The first thing you should know is if you run afoul (pun very much intended) of the law, I can’t bail you out. If you read the “About the Author” page on MentalMunition.com, you’ll note that I’m not a lawyer. My only legal qualifications are an undergraduate course in media law.

Having said that, I started researching drone law and writing back in March, shortly before the Brookings Institution organized a panel on domestic drones and privacy. The ACLU had just published a report in December 2011 called “Protecting Privacy from Aerial Surveillance: Recommendations for Government Use of Drone Aircraft” that referenced important Supreme Court cases that might play a role in drone law.

Just this week, Alexis Madrigal, the senior editor for the Technology channel at the Atlantic, wrote about two cases that could have some bearing on drone law, Guille v. Swan, and U.S. v. Causby. The latter involved dead chickens.

I’ll be writing about that case here. When we talk about drone laws, we’re talking about a speculative thing. To date, no journalist has been sued for violating rights of privacy with an unmanned aerial system. There is no legal precedent specifically for drones as of yet, although that might change in the near future. As drone technology proliferates, so too does the potential for abuse and for court cases.

But the United States courts are not absent of precedent that would come up in a privacy case involving drones. It’s is important to keep in mind that in many cases drone journalism is a form of aerial photography, albeit an unmanned form of aerial photography. Additionally, cases that consider whether the National Airspace System (NAS) is public or private are highly relevant.

Tags:

Alexis Madrigal

,

Atlantic

,

drone journalism

,

drone law

,

drones

,

privacy

,

U.S. v Causby

Friday, August 24, 2012

Drones are monitoring sea mammals, keeping tabs on oil spills, helping governments prevent floods.

Every year, AUVSI, the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International,hosts the biggest conference and trade show for drones in the country (but don't call them drones there; the term is UAS, for Unmanned Aerial Systems, please).

The industry group's last convention was in Las Vegas, and wrapped up earlier this month. A colleague who was there sent me the exhibition catalog. As is the custom nowadays, you could have read all that info online. But the printed version was still worth reading, and served as a snapshot of the "state of the drone."

I've taken four of what I thought were the most interesting talks, and pasted their descriptions here. The list includes researchers and developers using drones to monitor oil spills and the health of marine mammals. In one discussion, a Thai UAV company claims their technology helped the government make decisions that averted a major flood from inundating Bangkok.

Tags:

AUVSI

,

drone mapping

,

drone research

,

drones

,

NOAA

,

ScanEagle

,

sUAS

,

UAS

Tuesday, August 14, 2012

Get the fire extinguisher! Drone safety, GPS spoofing, and how I learned to stop worrying and love the drone.

There are certain things you expect when you're building drones for photomapping and journalism. First, you expect some setbacks. Perhaps a crash or two, or at least a few broken props. At worst, you expect a drone to take a fatal nosedive into a field and break into a hundred pieces, never to fly again.

There is a learning curve to this stuff. But you don't expect your drone to go haywire and burst into flames while you're working on it.

Last month, I was busy preparing an electric-powered drone in my basement for a maiden flight. With a wingspan of over 5 feet, and weighing a little over 7 pounds, it was the largest drone I've worked on yet, and it had a decent-sized power source to match.

Much larger drones have flown on the same basic technology, with power sources of twice the capacity used here. Most of our development to this point has focused on battery-powered drones instead of methanol-powered drones, because we want to keep the risk of fire down (even though fuel fires are rare). But that doesn't meant that batteries can't catch fire.

For my drones, I use lithium polymer batteries, or "LiPo," and they're pretty advanced as far as battery technology goes. They run today's electric cars -- the Leafs, the Teslas, the Fiskers and Volts. If you are reading this on a smartphone, you can thank a lithium battery.

Most other cells are contained in cylinders, but lithium polymer cells come in individual pouches. LiPo batteries are packs of lithium polymer cells that have been bound and tightly wrapped together. What really sets LiPo batteries apart, however, is the amount of energy they can store.

Whenever you're storing a great deal of energy in a compact space, and you suddenly release all that energy, you're liable to create tremendous heat. Since LiPos hold a lot of energy, under the right conditions, they can also catch fire.

According to the instructions of the original balsa plane I was hacking into an autonomous drone, the motor and its speed controller required 5 LiPo cells. I did not have a five-cell LiPo pack. I did have two 3-cell packs, and one 4-cell pack (which is quite large). Thanks to fuzzy math, I somehow thought it was safe to use the 4-cell pack and a 3-cell pack, for a total of 7 cells.

Everything seemed OK at first. The motor whirred happily during testing. Then I took the drone back to the basement to finish mounting and calibrating the autopilot, and things got weird.

Subscribe to:

Comments

(

Atom

)